Introduction

This is a civic handbook for the United States. If you're an American citizen and you are considering putting effort into staying informed, casting good votes, and volunteering or donating to some political activities, then this guide is for you - even if you don't plan to prioritize politics as the main focus of your life.

If you are an American who isn't very interested in politics and doesn't have time to read this whole article and follow its many recommendations, then skip it and read this instead - How To Be a Good Low-Information Voter.

Part 1: How to think about American politics

Getting Informed

People disagree a lot on politics. How do we go about finding the truth? As a precursor, you may want a good grounding in ideas of sound thinking. According to UK government advisor Dominic Cummings, "if you're young & want to change politics on the scale of 'do Brexit' I strongly advise you to read books like Julia Galef's Scout Mindset." You also need a basic understanding of social and global priorities as determined by the EA community. And pay attention to what the EA community has to say about politics: look at the 80,000 Hours Podcast, Julia Galef's Rationally Speaking podcast, Scott Alexander's blog, my website right here, and politically oriented EA groups on social media, and follow at least some of them.

Once you get the right mindset, just being in the loop of the EA community should be enough to keep you informed about the things that matter for the average citizen. If we need to vote a certain way on a major upcoming election, lobby the government to do a better of producing and distributing vaccines, or push some new animal welfare legislation, you'll probably get what you need to know from others in the EA community. And for local politics, follow local EA groups and YIMBY clubs. This is far easier than poring thru generic news feeds in the hopes of finding the rare opportunity for effective activism.

And contrary to the opinions of elitists and gatekeepers, making good decisions about politics doesn't require following the news. In some cases, it's waste of time to study political controversies in detail, for two reasons. First, there is often high quality evidence or common sense in favor of a particular side, so detailed analysis is unnecessary. Secondly, the chance that your vote (or letter to a representative, etc) will make a difference is quite low. Based on my estimate that 390,000 lives were at stake for the 2020 presidential general election, the average American vote would "save" (or destroy) 0.0062 statistical lives. Of course things are more complicated because of the Electoral College, but let's just use the average to illustrate the principle. One could just as easily save 0.0062 statistical lives by donating $20 to a GiveWell-recommended charity, so we can say that an average vote is worth about 20 dollars to an Effective Altruist. Now we could use this figure for a full expected-value calculation of the value of information for deciding how to vote, but let's put it in simpler terms with an analogy. You're going to play poker next week and you plan to bet $20. You can, if you want, research the game ahead of time to increase your chances of winning, but how much time are you going to spend doing that? Maybe spending half an hour would be worth it to increase your chance of getting a nice payoff, but spending several days would clearly not be worthwhile. Similar prudence should apply to politics.

You may judge it appropriate to study some political issues in detail. However, in this case you should do it deliberately as a sort of research project. Start with the question you want to answer (e.g., "who should I vote for mayor?") and then deliberately seek out information which helps answer your question (e.g., the candidates' websites, and all previously published stories about them). There's no point in passively browsing a news feed in the vague hope that one of the stories you see will one day be relevant to something important - chances are, if a story ever does become relevant, you'll have to go back and refresh your memory anyway. In the meantime, much of your time will be wasted.

What's the harm in reading too much news? First, even on the most factually accurate news sites, the vast majority of what you read is not useful. Sometimes it's punditry that can safely be ignored in favor of better sources, particularly when there are efficient markets: don't pay attention to warnings about recessions if you can just look at the stock market, don't pay attention to arguments about the inflation outlook if you can just look at the market spread for Treasury bonds, and don't pay attention to election predictions if you can just look at a betting market. Even if an efficient market is not available, there are often good sources which outclass punditry. For instance, Metaculus forecasts can evaluate future possibilities, and think tanks publish indices for different countries' performance on things like corruption and freedom.

Other news is not useful because the topic is simply irrelevant to us. There are some issues that most citizens simply can't or shouldn't try to fix. Some political issues are really just a waste of time and a distraction from more important issues. The constant controversies of the political cycle as partisans bash each other can mostly be ignored. Additionally, unless we need to take immediate action, anything about a developing story can be ignored as we wait for the full story to come out later. A big chunk of news coverage describes indictments, subpoenas, testimonies, pending investigations, promises, threats, draft bills, campaign speculation, and other stuff which is still pending a final outcome. All this news can safely be ignored by nearly everyone - just wait for the full story to come out later.

In fact, systematic studies tend to show that being more knowledgeable doesn't make you a better voter. Reading the news may narrowly help you if you use it appropriately, but it can equally hurt you if you're not careful. High news consumption is correlated with a systematic bias of overestimating the extremism of one’s opponents, and being too online can poison your mindset and inhibit you from making persuasive political appeals. Some people think that news is harmful and avoid it altogether, which is generally fine.

To further illustrate the point, let's look back on the top national and global political stories of 2016-2021 (a particularly tumultuous period of American politics) and consider with the benefit of hindsight whether the average citizen needed to follow them. Certainly, one should have been basically aware of the mass killings in Ethiopia, Burma, Syria and Iraq and understood the general outlines of those conflicts, one should have recognized the Chinese repression of Uyghur Muslims and one should have been loosely aware of the status of the war in Afghanistan - this is all a matter of basic moral hygiene if nothing else. The COVID-19 pandemic and certain policy issues associated with it, and Trump's attempt to overturn the 2020 election, were certainly things that every good citizen ought to have understood for basic civic reasons. And it was important to know that Democrats deserved votes over Republicans. However, that's approximately where the need for information ends. Trump's impeachment scandals may have warranted attention, but there wasn't much for ordinary Democrats to do there; simply deciding to vote against Trump was far more important. The murder of George Floyd and subsequent protests could have been safely ignored; those protests may have done more harm than good, and in any case criminal justice policy is of only moderate importance compared to other policy issues on which we have to focusThe singular event of the murder of Floyd did not intrinsically deserve attention by the average citizen - it is unnecessary and impossible to pay attention to every single case where a government agent wrongfully kills someone, and in any case we already have prosecutors, judges and juries to provide fair trials for them. Of course, the 2021 protests were really about more than just Floyd, they were about bigger problems of police brutality and alleged anti-Black racism, for which Floyd was a symbol. And criminal justice policy is a real, significant issue for America. However, it's still one of the less important policy issues compared to things like housing, immigration and animal welfare, and certainly far less important than great humanitarian crises like COVID-19 and genocides. Additionally, the protests had very dubious side effects. A minority of the protests led to substantial violence and looting, and even if we don't intend for our protests to end up that way, we should recognize the risk that our activities could inadvertently provide cover to bad actors looking for a chance to start violence. The protests also indirectly led to an increase in murders, disrupted daily traffic and commerce, and may have worsened the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, the protests did have some positive results - they accelerated some beneficial police reforms, and they seem to have encouraged more people to vote for Democrats. Overall, joining the protests would be a defensible choice, but my point is that ignoring the whole affair would be equally defensible. Those who take a particular interest in crime and policing can keep track of this sort of thing, but the average citizen does not need to stay updated on it.. Drama between Trump and journalists, drama within the Trump administration, the US-China trade war, Supreme Court appointments, Supreme Court rulings, Russia intervening in the 2016 election, Facebook controversies, #MeToo scandals, the Charlottesville protest and violence, the death of Jeffrey Epstein, Greta Thunberg giving speeches, Jussie Smollett pretending to be the victim of a hate crime, Colin Kaepernick kneeling during the national anthem, and other stories were all short-term firestorms to which the average person was not morally behooved to pay attention. If you disagree, then consider: what did you actually do about these events, and did it actually make enough difference to justify the hours you probably spent looking at news or social media?

One benefit of frequent news-watching is that it lets you track the reliability of forecasts and narratives. You can get a better sense of how often a rumor turns out to be true or false, how often people's predictions turn out to be right or wrong, and how quickly various events unfold. It is a good bit of wisdom which you don't get from historical narratives. But for most people I think it probably doesn't outweigh the costs and downsides.

Of course, the EA community would not be a good network for political action if none of us did anything more than the bare minimum to be politically informed. However, average EAs becoming generic online partisans is not the best way to keep the community sharp. It's better to develop specialized expertise so that the rest of the community can rely on you. For instance, if you live in Alaska, you could try to be a community expert on Alaskan politics. If you are a truck driver, you could try to be a community expert on trucking laws. If you are very interested in space exploration, you could try to be a community expert on space policy. Cultivate a deep understanding of one or two things and build a reputation for deep knowledge and sound judgment about them. The EA community has benefited greatly from possessing numerous individuals with strong knowledge of animal welfare, housing policy, and macroeconomic policy, and we should extend this pattern to more policy areas.

(To be clear, I am not saying that no one should have a full and broad understanding of politics. People like Kelsey Tuoc, Matt Yglesias, David Shor and Dylan Matthews make very good contributions, and I try to cover practically every political issue on my website. My point is that the average person doesn't need to follow in these footsteps in order to be a responsible citizen.)

When you do decide to read about a political issue, I don't recommend that you must refer to any particular political theory, research or news source. Frankly, it's not healthy for our community to rely on a particular selection of sources; better for different people to explore and see what they like best. But I do have a few general recommendations.

First, I advise you not to spend time listening to your acquaintances and family members about politics, and I certainly recommend that you don't go out of your way to befriend people with differing political views for the sake of hearing them out. These activities typically aren't harmful, but they are frankly a poor use of time. The Internet makes it possible to find the sharpest people and the most comprehensive political arguments, so a typical social circle won't help you much. David Shor says "trying not talking to people about politics and instead just vibing is a better way to learn about politics than trying to talk to people about politics". While being too exposed to social media can give you a distorted view of the political world, the simplest solution to that is to spend less time online, not more time everywhere else.

Second, while I don't positively recommend that you read anything in particular, I also recommend against dismissing most sources out of hand, and I recommend that you not worry much about arguments over whether media is biased. Always remember that the important question to ask yourself is not "what is wrong with this source?", it's "how can I learn from it?" You can morally judge the media if you like (and you obviously should if you plan to work for or donate to a media organization), but your primary responsibility as a citizen is to simply use the media to help you become better informed. So don’t shut yourself off from sources with different worldviews. It’s best to be open to what you see shared by a variety of decent sources, expect them to have some shortcomings, and learn what you can nonetheless.

For the reliability of news and editorial journalism, see Ad Fontes Media's ratings of different news organizations. The most reliable sources are straight reporting agencies like Associated Press and Reuters. Other mainstream media is generally pretty reliable. So is most local news media, although Ad Fontes doesn't rate it. But opinions and analysis can be equally valuable even if they don't get high ratings for reliability. Personally I would divide sources into two groups above and below the line running thru the middle of the chart linked previously. Sources like Jacobin, Slate, Russia Today and National Review are the minimum tier of media worth reading. Everything below that is not necessarily 'fake news' but does tend to be useless muck that you can safely ignore. I would also say that many op-ed pages on otherwise reliable mainstream media outlets are nonetheless at about that same minimum tier of media worth paying attention to. Note: as long as you have an appropriate basic element of trust in mainstream sources, the risk of being misled is much less than the risk of being distracted. With a few notable exceptions, media and pundits do more damage by asking the wrong questions than they do by providing the wrong answers. Be wary of outlets and commentators which focus on the media and political culture rather than the dilemmas of political power, make petty accusations of hypocrisy rather than strictly advocating their own principles, or speculate on the motivations of their opponents rather than the consequences of their opponents' actions. Their ideas are often correct, but only rarely can they actually help you be a more effective citizen.

Think tanks vary in quality, but the same advice generally applies to be open-minded to all of them. Whether think tanks are part of the mainstream Washington D.C. establishment, or ideologically beholden to left-wing activism, or supported by dubious right-wing funding, they can and do produce analyses that can help you learn - although sometimes you will have to apply a more skeptical filter.

Academic research can provide the highest quality analysis in theory, and of course should never be dismissed out of hand, but still can be unreliable with flaws such as publication bias.

Here is a list of some helpful resources:

- Spreadsheet with a collection of resources about weapons of mass destruction

- Jennifer Doleac's spreadsheet of crime-related papers published in top econ journals

- My Twitter list of US domestic policy think tanks

- Guide to circumventing paywalls for research papers

Priorities for Government

Political disagreements can be very intractable as people make arguments from widely differing implicit perspectives about the role of government. What matters more, rights or welfare? And whose rights matter most? Whose welfare matters most? How much responsibility do we have to help the poor? To help people in foreign countries? People often disagree on these foundational issues, making political disagreements very intractable. Yet they will often elide tension by claiming that their preferred policies are better for practically everyone’s rights and practically everyone’s welfare. (Sometimes this is true, more often it isn’t.) People also often choose their political loyalties and preferences first and then select whichever philosophical principles best support them. But we can do better by building upon the excellent progress made by the EA community.

Moral Foundations

EA provides a coherent set of principles to guide our altruism, which we can extend to political engagement. As a starting point, of course, we must care equally about every human regardless of their ethnicity, their country, their intelligence, the amount of taxes they pay, and similar distinctions. We must also care about animals, given the good evidence that many of them are conscious like us. And we need to extend this concern to people and animals of the future. So for example, when we talk about taxes we should consider how they will impact people in the future, and when we talk about trade we should consider how it will impact people in other countries.

We should also care about all people and animals in accordance with their actual desires. We should pay attention to happiness surveys and other methods of revealing people’s welfare and interests, and we should not use philosophical constructs like rights to marginalize other issues. So for example, if we are debating whether we should raise taxes to pay for more public education, we should not focus on whether people have a ‘right’ to get more public education or a ‘right’ to pay less taxes to the government. Instead, we must look at the scale of benefits and the scale of costs and make a judgment as to which one outweighs the other.

If you take these principles to their full logical conclusion, you get the moral theory of utilitarianism. Many Effective Altruists don’t do this, and believe in exceptions such as adopting an ethos of loyalty, protecting key human rights at all costs or rewarding people differently depending on their moral character. And that’s fine. You can get into plenty of philosophical debates about these things if you want, but we can usually address practical political problems just fine without agreeing on life-and-death ethical thought experiments. Dilemmas in the real world are not like the ones in introductory ethics books. We don’t live in Omelas.

However, it is critical that we preserve a basic ethical concern for everyone. There are some people whose idea of Effective Altruism is that it is just a tool for being more effective at helping whoever they already care about. In the ordinary context of charity, this is sort of tolerable. If someone just wants to donate to whatever charity best helps Americans for instance, that does far less good than if they donate to the globally best charities, but it's still better than being selfish or irrational about charity. Yet in the arena of political conflict, if people only care about helping their own group, they may support policies and candidates which are actively destructive to everybody else. So we must promote a clear commitment of benevolence towards everyone.

Such a commitment still isn't enough to resolve all political disputes. When we face tough political questions, they are things like “should we continue our deployments in Iraq” and “is a wealth tax better than a capital gains tax” – complex issues where actions cannot be decided thru simplistic appeals to moral principles. The real difficulty lies in setting practical priorities for global welfare and using social science and careful reasoning to judge which policies will best meet them.

Fortunately, a good deal of informal debate and formal research in the Effective Altruist community has addressed the problem of setting practical global priorities. The result is that we’ve identified three general categories of things on which actors such as the government should focus.

Stopping Immediate Suffering

The government has significant power to alleviate – or cause – large losses of life and welfare. Extreme poverty is a severe problem. One in ten humans lives on less than $1.90 per day, with many breaking just a little above this low figure. Diseases such as AIDS and malaria are also enormous global crises. War is not just responsible for death and injury, but also displaces huge numbers of people as refugees. Finally, animals face extreme hardship both in captivity and in the wild.

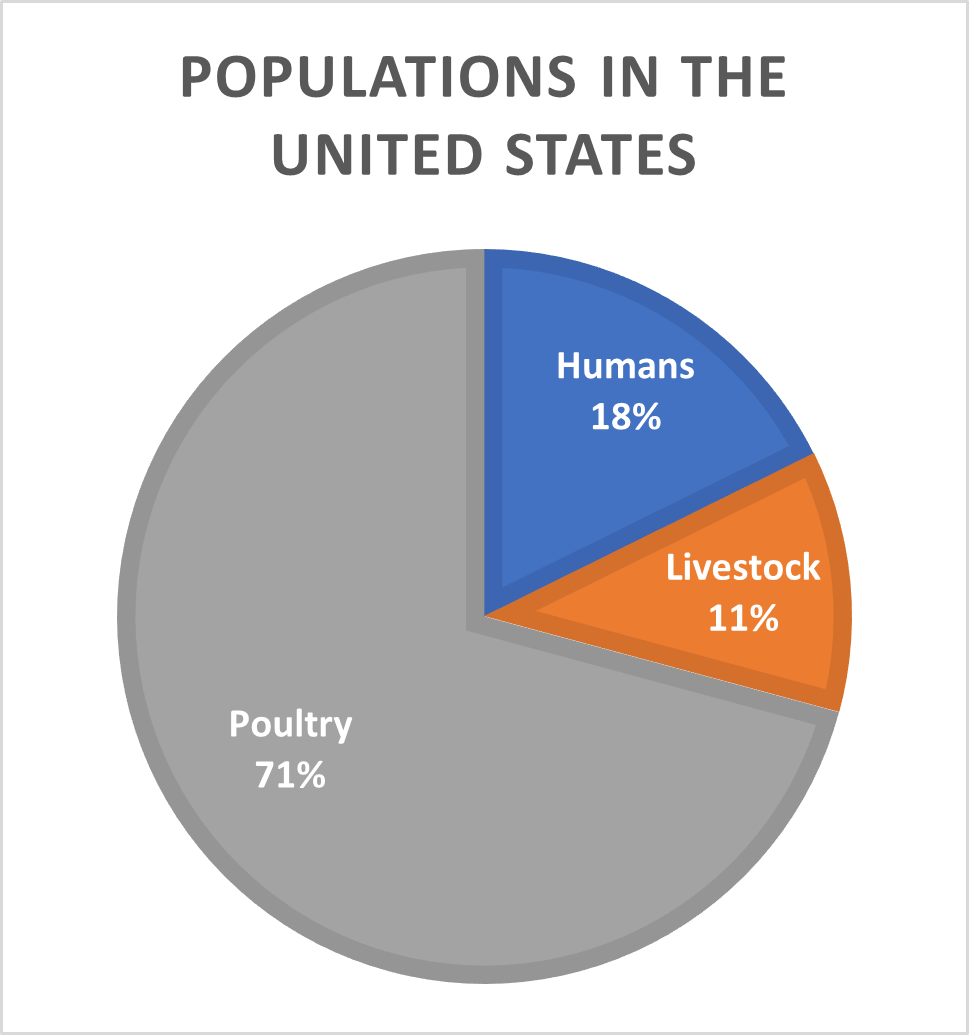

This does not mean we should be pessimists. Ruut Veenhoven has summarized findings on happiness, and it turns out that most people in the world are reasonably happy and are getting happier as society progresses. Improving welfare in society does not require abolishing social categories, achieving economic equality, ending modernization or ending individualism, although economic redistribution is still a great way to fight poverty. And environmentalist concerns about overpopulation, resource consumption and pollution are not strong enough to justify hesitancy about saving lives and ending poverty. But one critique that is worth paying attention to is that reducing poverty tends to increase meat consumption This is known as the "meat eater problem." See this paper for some of the basic economic evidence of the pattern. See this EA Forum post for a welfare analysis comparing the benefits of poverty reduction with the harms of factory farming. .

Improving the Long-Term Future

Future generations are very important, so it is important that we take actions which will set humanity on a better trajectory. One way to do this may be to promote economic growth, though this is debatable. Growing the economy of the United States or democracies in general, or uplifting the poorest countries, may be more valuable in the long run as it could lead to freer and equal system of international politics.

Domestic economic inequality is a common concern, but we should separately consider vertical inequality and horizontal inequality. Vertical inequality is differences in income among individuals, as measured by the Gini coefficient. It actually does not seem to cause many secondary social illsSee this paper and this article. However, vertical inequality represents an opportunity to reduce poverty, typically by taxing the rich to pay for social programs (redistribution), and maybe by making the economy work in ways that allocate income more evenly in the first place (predistribution).

Horizontal inequality meanwhile is a systematic difference in income between groups. Horizontal inequality can cause substantial secondary social ills. The most notable case of this in the United States is the substantial gap between whites and African-Americans. In fact, poverty is so closely connected with ethnic status in the United States that colorblind programs of economic redistribution would substantially reduce the ethnic wealth gap as well.

Gender equality does not substantially improve happinessA 2018 metanalysis found that gender equality in a country predicts greater job satisfaction for women, but not life satisfaction. A 2009 study showed that women's happiness relative to men in the United States has been declining since the 1970s, despite this being a time of increasing gender equality. The lack of results may be due to harm inflation: as older, more severe forms of oppression disappear, people become more sensitive and vulnerable towards milder infractions., but can improve political systems and reduce conflict. Democracy similarly does not cause happiness, at least not directly, but can improve economic growth, prevent crimes against humanity, and reduce war.

Reducing Existential Risk

Existential risks are arguably the most crucial problems that we face. In spite of pessimistic criticisms of the downsides of human civilization, saving humanity is in fact a good thing.

What doesn't matter

We should also explicitly recognize some particular ideas which shouldn't guide our policy opinions. First, we shouldn't treat compromise and consensus as core political goods. Don't reject policy just because half of the country doesn't want it. (You can defer to collective opinion with the principle of epistemic modesty, but in this case you should probably look at what experts or Effective Altruists have to say, not the entire electorate.) The way that democracy works is that people demand different policies and then the dispute is resolved thru peaceful elections; it does not fall upon partisan actors to give up in deference to a lack of consensus.

And of course, we shouldn't base our policy opinions on how they would impact ourselves or our communities. It's one thing to disavow parochial moral opinions, but quite another to actually follow universal ethics in a way that is unbiased in practice. People who fight for parochial interests often self-aggrandize or adopt clever arguments to show that their preferred policies are best for the collective good. So keep a sober perspective on your unimportance relative to the rest of the world. For example, the Effective Altruist community is excellent relative to its size, but if a change to the charity tax deduction threatens our donations, we shouldn't judge that primarily in terms of how it affects us, since we represent only a very small proportion of all philanthropy.

Part 2: What to Think About American Politics

Issues

Political engagement requires judgments on which policies are good or bad as well as judgments on which policies are a greater or smaller priority. You may have some strongly held views here already. But it’s healthy to be suspicious of your prior assumptions, especially if you adopted them before you became more politically literate or before you adopted the ethical and methodological principles of Effective Altruism. If you are learning more about policy now, think of it as an exciting opportunity to obtain a different point of view.

Here is an overview of the mainstream political issues which I recommend as being the highest priorities for EA attention. If one political candidate is much better than the other on these topics, then it’s reasonable to say that she’s probably better overall. In this section I only give a basic overview of these policy issues, but if you want to see more detailed and comprehensive arguments then refer to my full policy platform. Also, note that while I focus on overarching policy goals, the gritty details of policy implementation are also very important.

Foreign Policy

The importance of our foreign policy is easily understood. The United States is the most powerful nation in the world. Our diplomatic and economic engagement greatly affects many countries. In crisis-torn regions, the stakes of US involvement are high – and they are often higher than the stakes of our domestic policymaking, at least in the short run. Americans generally recognize this, whether they support America’s foreign policies or not. Yet these matters get relatively little attention in our politics. Sometimes this is because voters just aren’t concerned about foreign policy in the way that they worry about policies that directly affect them and their countrymen. It is also because many voters overlook the complexity of these issues. Simplistic demands to ‘end the forever wars’ or to place ‘America First’ discourage serious and responsible understanding of global problems, thus perpetuating an absence of cogent new foreign policy platforms for policymakers. Finally, some Americans are understandably cynical that their voices can influence foreign policy, when their legislative representatives play little role and the executive branch operates with relatively little oversight and transparency.

But this neglect of foreign policy provides opportunities for progress. If we understand how to improve America’s international engagement, not only will we be smarter voters, but we can also provide viable solutions for the directionless public and the sclerotic government.

Perhaps the biggest priority in foreign policy is nuclear security, as a large scale nuclear war could kill billions of people and wreck human civilization. We must minimize the risk of nuclear war and, if that fails, mitigate its scope and consequences. The largest nuclear arsenals are possessed by Russia and America, while China is in distant third but quickly expanding. Nuclear weapons held by minor powers around the world also pose risks. So naturally we should pursue nuclear arms control treaties for mutual security. Practically everyone agrees that this is a good idea in theory, but Effective Altruists can improve the conversation about how to do it responsibly and effectively, and hold presidential administrations to account for missteps.

There are also questions about we should manage our own nuclear arsenal. Not everything is regulated by a treaty, and sometimes other countries just aren't interested in good mutual reductions. Therefore, our government must make decisions about how to shrink, expand or modernize our nuclear forces. I would advise against naive views that a small nuclear force is just as effective at deterrence as a large one, or that 'mutually assured deterrence' assures peace. If we want to improve nuclear security then it behooves us to understand modern deterrence theorySee this reading list. and account for the ways that a stronger, weaker, or qualitatively different nuclear arm can impact international politics. And since the constitution of America's nuclear arsenal has ramifications for international politics, our judgments about it must depend on whether we support or oppose America's goals in international politics.

Because of these considerations, I believe that many members of the EA community to date have held some incorrect views and made some misguided statements about nuclear weapons. In my view (which is the same as that of many nuclear experts), ideas like unilateral arms reduction and 'no first use' declaration would likely do more harm than good. These are important questions and we should have robust informed debates about them, so give them the appropriate level of research and critical thinking.

Conventional military forces also have important ramifications. They can affect nuclear security; in particular, a larger conventional military can reduce our reliance on nuclear weapons and reduce the risk of nuclear escalation, at least in some circumstances. Additionally, we must think about the goals of the United States in international politics and whether it is worth spending more money to support them with force, and we must think about wars that are fought and are likely to be fought by the United States and consider whether it is worth spending more money to help win them. One of the biggest priorities is to protect Taiwan's right to self-determination against Chinese pressure and invasion.

This all brings up the question of what America's goals in foreign policy are, and what they should be, beyond a basic commitment to the immediate military security of the homeland. Clearly, America should take a stand against governments and militants who perpetrate mass atrocities. Genocide as seen recently in Iraq, Rwanda and Bosnia, the concentration camp system in Xinjiang, and man-made famines as seen in Yemen and Tigray demand serious responses. Many other parts of the world have more chronic problems of violence, intolerance and oppression, and the world is further threatened by Chinese aspirations to revise global governance to accommodate its political ideology. We can take a variety of actions to address these issues.

Foreign policy debate often revolves around the idea of military interventions to fix such problems, but keep in mind that America's current military operations are extremely limited compared to the wars of the 2000s and 2010s. America today has 2,500 troops in Iraq and 900 troops in Syria, generally in noncombatant roles, besides the many thousands of soldiers in more stable places around the world. We also conduct counterterrorist raids and airstrikes in various places around the world.

These are mostly benign, common-sense missions that mitigate extremist and revanchist threats at relatively little cost to the taxpayer and soldier. However, it is worth questioning whether some of our bases are unnecessary, and whether raids and strikes need stricter oversight to mitigate collateral damage.

Future crises may spark debate over whether the United States should militarily intervene in a big way to shape conflict outcomes and change regimes. Before making such decisions, we should pay attention to the lessons of history. You presumably know about how the invasions of Iraq in 2003 and Afghanistan in 2001 turned into very long and costly affairs, so that probably the majority of informed people now regard them as mistakes. That said, our judgment should also be informed by the history of other military interventions, such as those in Libya, Bosnia, and Kosovo, and we should consider the consequences of nonintervention in cases like the Rwandan Genocide and the Syrian Civil WarAmerica did intervene by providing arms and training to rebel groups and launching air strikes, but this was a limited effort that was mainly done against ISIS. We also did launch some attacks against the Syrian Armed Forces in retaliation for their use of chemical weapons, but this had almost no real impact on the conflict. The bigger issue is that the US did not intervene to bring down the Assad regime, and some believe that the atrocious conflict and crimes against humanity which followed would have been mitigated had we taken such an action, though of course this is debated.. We should also obviously pay close attention to the specific context before making decisions about intervention. Military operations cost American lives and money and can actually produce a significant amount of pollution, so they need to have large potential benefits to be justified. Unfortunately, there are no easy answers here. Making decisions about military interventions requires careful consideration of the particular situation, looking at factors such as public opinion in foreign countries, the prospects for success, the quality of governance offered by different regimes, the broader regional and strategic implications of the war, international law, and the lessons we can learn from history. This complexity can be discouraging to those of us who want to make a clear positive impact thru superior policy judgments, but if we do not engage with these issues then the outcomes of other people’s deliberations will probably still be worse. As an alternative, we can pursue peace agreements, but we cannot wrest real concessions from an enemy if we are not credibly willing and able to beat them in war. The critical barrier to civil war settlement is the presence of a foreign mediator that can credibly threaten the use of force to back up an agreement, and the United States can play that role, although we failed to do so in Afghanistan.

Not everyone has time to do the appropriate level of research on military interventions. You don't need to know details of American military doctrine and technology, nor the intricacies of foreign cultures, nor decades upon decades of history in order to reach good conclusions about foreign policy, but you do need to put in a good deal of research and thinking about the state of the foreign country and its possible futures. If you still want to have a quick and simple rubric for judging military interventions, my advice is to ignore all punditry, which is usually garbage that does not simplify the issues in appropriate ways; instead, just look to surveys of public opinion in the countries where intervention is being considered or conducted. Usually you can find a few opinion polls by reputable agencies. If not, you might get a decent sense just be browsing media and social media for what they have to say. If a large majority of people support the intervention into their land, then you can presume that it's a good idea; if only a bare majority support it then you can presume that it's good in theory but not worth the sacrifice of American blood and treasure; and if a majority oppose the intervention then you can presume that it's harmful. Of course, this carries many caveats, such as the fact that sometimes it is good to intervene to protect a minority being oppressed by a majority, and the fact that we should still pay some attention to American interests and our preferred world order rather than only thinking about military interventions in terms of local interests and humanitarianism.

Keep in mind that choosing when and whether to go to war is just one half of the military equation; we also have to actually win. And even when American military interventions are ill-advised, it is still better that we win rather than lose. For instance, imagine how much better off America and the world would be if we had successfully defeated the insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan. Not only does this require better leadership and execution of military operations, it also involves contributions by the intelligence community and civilian agencies of the government. As Tanner Greer writes, "the war in Afghanistan is not the failure of a man, or even of a few men, but of an entire leadership class." We can contribute to making all relevant components of our government work better.

Other components of foreign policy are arguably just as big of a priority as military affairs. America must do a better job with targeted sanctions, diplomatic negotiations, multilateral treaties and other efforts. It is pretty clear that the State Department should get more funding and improve its methods so that we can do more to peacefully support prosperity, freedom and democracy around the world. Also, an underrated tool here is to accept refugees; setting aside the broader questions about American immigration policy, there is an unequivocal moral imperative for us to provide a place of refuge for those fleeing severe persecution, which is only bolstered by the fact that such people will be more grateful and patriotic than anyone as they are saved by our country.

Foreign Aid

Support politicians who endorse aid to the developing world. Our best programs are in the realm of global health. PEPFAR has saved millions of lives. A few Republicans – especially populists such as Donald Trump and Rand Paul – have tried to cut foreign aid. But foreign aid funding is more often a bipartisan issue; PEPFAR was started by President George W. Bush.

Animal Welfare

Animals are probably conscious and therefore deserve our compassion. Most animal farming in America appears to be negative in welfare – in other words, the animals' lives are so bad that they should never have been born. Even when farms have positive welfare, there is still a frequent need for stricter regulations to improve their quality of life.

Jacy Reese’s book The End of Animal Farming (interviews here and here) describes how scientists, activists and entrepreneurs can collaborate on these issues. Reese’s recommendations include focusing more on innovative meat replacements rather than promoting vegetarian diets, focusing on changing institutions more than trying to persuade the public, and focusing on teaching people how to eat ethically rather than arguing why they should.

The Humane Society Legislative Fund compiles scorecards of legislators’ actions on bills affecting animals. Some of HSLF's judgments are debatable or simply unimportant, such as bills about hunting or service dogs, so look into their scores carefully rather than taking them at face value.

A moratorium on factory farming construction may be achievable soon. Numerous Democratic 2020 presidential candidates endorsed the idea. It can also garner support across the partisan divide: factory farming has been repeatedly criticized by conservative publicationsSee the National Review articles by John Connor Cleveland, Spencer Case, and Matthew Scully, and the American Conservative article by Eamonn Fingleton. for being cruel, unnatural, and a center of corporate corruption. Focusing on these perspectives, as opposed to talking about animal equality and rights, may allow for broader cultural appeal with American voters.

The government should also promote R&D for meat replacement foods. The Good Food Institute has worked in this area.

Politicians rarely say much about animal welfare, so we sometimes have to look at their political party and identity to guess whether they might be good on this issue. It is clear that Democrats usually do a better job of protecting animal welfare than Republicans. A few Democrats such as Cory Booker and Tulsi Gabbard have publicly proclaimed ethical commitments to veganism. Moderate Republicans can still be better than right-wing ones; Susan Collins and Martha McSally have perfect legislative track records on animal issues. Politicians in urban areas are generally better on this issue than politicians in rural areas. Female politicians seem to be better on this issue than men on average.

Note that while animal welfare can get surprising amounts of support from poll respondents and conservatives, that doesn't make it a winning issue for liberal campaigns. The polls are not strong evidence of durable popular sentiment in this case, and most people just don't care very much about animal welfare even if they say they are in favor of it. So animal welfare shouldn't be front and center in political messaging, even though we should still keep it in mind as a crucial component of our political judgments and conversations with like-minded people.

Air Pollution

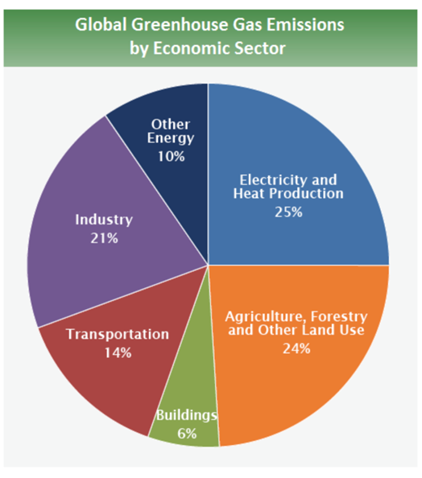

The problem of anthropogenic climate change is a scientific consensus, and past predictions of it from climate models have been accurate. Forecasters assign a 50% chance to global warming exceeding 2.9°C by 2100. Air pollution can also directly damage public health and crop yields and childhood learning. Studies estimate that 100,000 to 200,000 Americans, and probably millions of people around the world, die because of air pollution each year.

A theoretically excellent tool for fighting pollution is to tax polluters or dirty energy producers. Carbon taxation is widely supported by economistsIGM surveys of top economists show clear preferences for carbon taxes over emissions regulations and income taxes. A 2015 IPI survey of economists with publications on climate change found that 81% (figure 7) believe that carbon pricing is the most efficient way to meet climate change goals.. The ideal way to structure a carbon tax is to levy it nationwide and ‘upstream’ on energy producers while applying ‘border carbon adjustment’ tariffs on imports.

There is extensive debate on the political feasibility of carbon taxation. Passing a carbon tax would be significantly more difficult than modest measures to strengthen EPA regulations or increase clean energy spending and subsidies, but it could have a greater environmental impact. On the other hand, passing a carbon tax might be easier than passing an ambitious “Green New Deal” spending program, while being comparably effective.

Unfortunately, the political difficulties of passing a new tax mean that carbon pricing in practice can be quite flawed. And carbon taxes do have some economic downsides. While they are the most powerful single tool to address climate change and we should support them, we shouldn’t be fixated on them. Politicians who oppose carbon taxes can still do good work to reduce our emissions in other ways, and it may be better if we focus our lobbying efforts to focus on more tractable policies.

A more achievable and very effective policy is to promote clean energy R&D. This would be particularly beneficial for helping other countries reduce their air pollution too. Economists and policy analysts generally believe it is a good idea. Let’s Fund argues that it should be a higher priority than passing a carbon tax. Research into all forms of clean energy – including solar, wind, geothermal, and nuclear – can be valuable. Geothermal power is particularly politically attractive since it can provide jobs for people leaving the oil and gas industry. Clean energy subsidies, long-range power transmission, and energy storage are also important.

Numerous voters and politicians, particularly environmentalist ones (oddly enough), have a misguided hostility to nuclear power. But this should be judged in context of the fact that nuclear power is not necessary and more expensive than solar and wind, which are already cheap enough to revise our energy grid. Meanwhile, schemes for revolutionary improved forms of nuclear fission have dubious viability between cost and development time. The government should certainly extend licenses for existing nuclear power plants and include nuclear technologies in the broad portfolio of cleantech R&D, but acceptance of nuclear power is neither a requirement nor a panacea for fixing our energy economy, so we shouldn’t be extremely worried about anti-nuclear politicians.

We should also pay significant attention to agricultural and industrial emissions. Ramez Naam suggests establishing ARPA-A and ARPA-I research agencies for new agricultural and industrial technologies, and subsidizing the adoption of those technologies.

Carbon sequestration is also good – both advanced technology and simple tree planting.

Finally, international treaties can tackle climate change and other environmental problems. A widely supported move is for America to rejoin the Paris Agreement, but further engagement is possible. Other good moves are promoting exports of clean technology to the developing world and supporting the Green Climate Fund.

According to a 2020 metanalysis, attempts to change American minds about climate change are typically fruitless, but the messages that seem relatively promising are the ones that make climate change look like a concrete near-term problem, appeal to people’s emotions, or invoke Christian values and authority figures.

In this podcast, Yascha Mounk and Zion Lights discuss how to change people's minds to support environmentalist policy.

Housing

Have you ever wondered why so many American cities contain acres of suburbs rather than more profitable and affordable apartments? The reason is that city governments maintain zoning restrictions forbidding the construction of dense housing. The zoning laws are bolstered by a network of local activism known as “NIMBY” (not-in-my-back-yard) politics, consisting predominately of local landowning residents and special interest groups who stonewall construction projects that they don’t wantHomeowners may oppose dense construction because their home value rises when housing is scarce, because they don’t want newcomers to increase road traffic, because they mistakenly believe that new housing raises rent prices, or because they personally prefer the appearance of low density neighborhoods. Additionally, they often fear or dislike the idea of new people moving into their neighborhoods, particularly if the new housing is cheap enough for low-income residents who are often African-American or Hispanic. In fact, many restrictive zoning laws in the United States originated as racist segregation. This article gives a good overview of the early racist origins of American zoning laws, and this document has more details. Recent studies have suggested that exclusionary zoning was used as a tool for racial segregation in New York City, Chicago, and northern cities more generally. Needless to say, these are not good reasons to oppose new housing..

This leads to an increase in housing prices for both buyers and renters. When the quantity of available housing is artificially low, sellers and landlords naturally raise housing prices. If the worst-regulated city (Los Angeles) were liberalized to the same level of land restrictions as the least-regulated city (which is probably overly restricted in its own right), then housing costs would fall by 25%. Until then, the high rents exacerbate urban poverty.

Housing shortages also force more people to find housing away from cities, at the cost of receiving lower wages. The companies in cities cannot hire as many workers as they would like. This substantially damages the American economy. Multiple studies have shown that even a moderate, partial relaxation of our zoning restrictions would substantially increase America's GDP.

The political economy of housing restrictions is also pernicious. Samuel Hammond writes that it creates a split society: the elite who can afford urban housing get the best schools and jobs, as others languish in stagnated rural areas. Housing restrictions can also increase segregation between whites and African-Americans.

Housing restrictions are also detrimental to transportation and the environment. There are two general ways to lay out a city: suburban sprawl where people must rely on cars for long highway and road commutes, and urban density where people can walk, bike and take public transit. The latter tends to be more convenient for getting around, especially for low income people. It also reduces traffic accidents (which kill about 35,000 Americans each year) and air pollution from vehicles. Finally, dense housing further reduces pollution by reducing energy use, as HVAC and insulation are more efficient in large apartments.

The COVID-19 pandemic is sometimes invoked as a reason to forbid high-density housing. Dense housing supposedly aids the spread of infectious diseases. But this argument is backwards. Neighborhood-level density is not the problem; crowded households are. When housing is very expensive thanks to zoning restrictions, more family members and roommates crowd into the same housing units, thus spreading the disease more – even if they live in sprawling suburbs.

Our judgments on housing don’t just come from studies. Many Effective Altruists live in cities such as San Francisco where we get local experience of the high housing prices, byzantine approval processes, and diseased political economy associated with zoning rules. We don’t ever seem to disagree on the basic political question.

This all adds up to clearly show that housing restrictions actively undermine America’s economy and society. The obvious answer is to get rid of them. The problem is mainly caused by local governments, but state and federal politicians have increasingly recognized it and pressured cities to allow more housing. Achieving parking reform is another important piece of this puzzle; land use law expert Michael Lewyn believesComment in a 2020 Zoom chat. it can be a lower-hanging fruit than legalizing more housing.

Housing policy doesn’t end with land use regulations. Some argue for increased public housing: large apartments which are owned by the government, for the express purpose of providing affordable rental housing. But there are many problems with this idea.

Many people also invoke rent control as a solution to high rents. But strong rent controls discourage the construction of new housing, they reduce the incentive for landlords to maintain their properties, and they discourage residents from moving out of areas where other people have a stronger need to live. Economic research has consistently shown that rent control doesn’t work, and economists almost universally oppose rent controlsSee the IGM top economist survey and Greg Mankiw's economist survey.

So ending rent control policies seems like a generally good idea. But the reality is more nuanced in some contexts. In 2018, USC researchers argued that rent control has some upside because it promotes housing stability. Modest rules against rent hikes (for instance, a rule that landlords can only raise rents by up to 7% each year) can protect people from sudden hardship while avoiding causing major damage to the housing market. Also, in localities where dense housing is forbidden anyway due to zoning regulations, rents are artificially high and rent control may act as a sort of band-aid that still leaves room for an economic incentive to develop land as much as is legally possible.

Finally, housing vouchers are a way to help struggling families afford rent. They can be a good form of poverty relief, but economically speaking, it’s hard to see why we should offer specific assistance for housing when instead we can provide cash that people can use for whatever they want, like a basic income or integrated cash assistance. Politically speaking, housing vouchers may be easier to implement than cash transfers. Still, they can lead to increases in rents, and fail to fix the general economic problem of housing scarcity.

In summary, all three of these measures – public housing, rent regulation or deregulation, and housing vouchers – may be helpful in some contexts, at least when implemented properly. However, they do not present an adequate solution to the housing crisis and so they cannot eliminate the need for major zoning reforms. The evidence base in favor of zoning deregulation is also more robust than the evidence base for any other housing intervention. So zoning deregulation should remain our top priority.

Housing restrictions are a bipartisan problem which is especially entrenched at the level of local government, especially city councils. Neither Democrats nor Republicans make an adequate stand for housing reform. To fix the housing crisis, we need to engage in lobbying and activism across the board, and we need to elect specific politicians who recognize the nature of the problem. This can be difficult because homeowners tend to have strong selfish commitments and do not change their minds much when presented with arguments for new housing, but advocates still do better when they use economic arguments for building more housing, as opposed to using racial justice arguments. A burgeoning YIMBY (Yes-In-My-Back-Yard) movement has made real political progress, and California residents should get involved at the California YIMBY action hub.

Political Reform

In his article Why We Can’t Build, Ezra Klein argues that our political institutions are dysfunctional due to becoming a federal vetocracy where too many actors are able to block major action. The combination of stringent checks and balances, complex congressional committee system, Senate filibuster, ideologically polarized political parties, deliberate right-wing efforts to undermine the state, local NIMBY politics, and market short-termism have collided to create a crippling inability to take political and economic action.

There are some points where Klein’s view can be critiquedOne can argue that the left wing has also deliberately undermined state capacity by stonewalling security measures against illegal immigrants. One can additionally criticize the countermajoritarian structures of Congress and Electoral College for giving disproportionate veto power to small states (Klein would agree). Others will point to practices of lobbying, regulatory capture and rent-seeking which undermine the government’s ability to challenge the interests of large corporations and commercial/occupational associations. Finally, many economists would say that market incentives are much less risk-averse, and the government much less wedded to a capitalist logic of efficiency, than Klein believes. But overall it is pretty clear that our political system has grown into too much of a vetocracy. Recently, in the absence of a functioning legislative process, America has relied on executive actions and judicial activism to implement modest changes. But both of these are imperfect band-aids, and not just because of the limited scope of their abilities.

For one thing, political scientists and informed commentators seem to mostly agree that the office of the presidency has grown excessively strong to the point of being dangerous. It is one of the four recurring threats to American democracy. This has been a bipartisan problem, starting from the Constitution and growing over many recent presidential terms, but has come to a head with Trump’s attempts to manipulate the 2020 presidential election. The conventional wisdom is that we need to reign in executive powers and strengthen Congressional oversight.

Meanwhile, America's reliance on judicial power has been criticized by conservatives, liberals and leftists for subverting contentious issues to being decided by undemocratic processes. And recent right-wing appointments in the courts and bureaucracy may stifle general efforts at political reform for many years to come.

So what should we do? Klein says that we need patient, sustained, long-term efforts to reform our political institutions in ways that bias them more towards action and ambition. More specifically, he recommends ending the Senate filibuster, simplifying the congressional committee system, and ensuring that elected majorities can implement their agendas. We should also provide statehood for Puerto Rico and Washington D.C., to provide equal political rights to their residents and to reduce the unhealthy pro-Republican bias of the Senate and presidential election. There are also viable proposals to weaken the Supreme Court. Generally speaking, Democratic politicians seem to be more supportive of such reforms than Republicans are.

Another avenue for reform is to reduce the power of local governments and simplify bureaucratic procedures for construction (like impact reviews and public comment sessions). This would allow us to build more housing, infrastructure, and energy projects.

The political system can also be improved by changing our voting methods. Our dominant system of first-past-the-post voting, where voters just select one preferred candidate, is bad. Larry Diamond, a political scientist specializing in democracy, believes that replacing it is the single most promising reform for fixing American democracy. There is active debate on just what should replace it, but all the main alternatives are at least improvements over the status quo. You can help move the issue forward by taking action with the Center for Election Science.

The Political Parties

If you are very worried about political bias and tribalism, then the idea of identifying with a political party may be repulsive to you. But our political structure necessarily creates partisanship, and it is not going to change anytime soon. We may as well accept it. And there are systematic differences between the major parties, so it is very plausible that picking one and helping it win should be a high priority.

You may worry that affiliating with a group can bias your mindset in their favor, and there is inevitably some truth to this, but trying to perfect your rationality is less important than making a mostly-positive difference in the real world of power and politics. In practice, there are many political party members who disagree with the majority of their party on several issues; it’s perfectly feasible to have a dissenting opinion while retaining party membership and loyalty. Finally, people who try to stay aloof from party competition can themselves be biased to maintain a false narrative in which both sides are equally meritorious and equally deserving of respect. Such bothsidesism can be just as wrongheaded and pathological as blind tribalism. Instead, we must be hard-nosed about which factions are helpful or harmful.

The previous evaluations of major policy issues suggested that Democrats tend to be better on animal welfare, immigration, air pollution, and political reform, with the parties being more tied on some other major issues. For a more serious evaluation, see this systematic comparison which uses policy analyses and expert surveys to determine that the Democrats are superior overall. Of course one could find reasons to disagree, but that would require some serious arguments. Typical criticisms of the excesses of the progressive left for instance are not sufficient to change the big picture.

Politician Qualifications

In addition to their views on policy, there are other aspects of politicians which we can judge.

First, it’s good to support experienced candidates. The longer that legislators stay in office, the more skilled they become. Resist the layman wisdom that electing outsiders will make the government better. You would not hire a politician to run a business, so why would you pick a businessman to run a country? The skillsets are different. The root of sentiments against experienced politicians is that people observe our government delivering poor outcomes and then assume that it's because career politicians have some kind of personal shortcoming. But in reality, the failings of government are mainly due to partisan differences and structural incentives. Electing an outsider just means that someone inexperienced will face the same problems and will probably perform even worse.

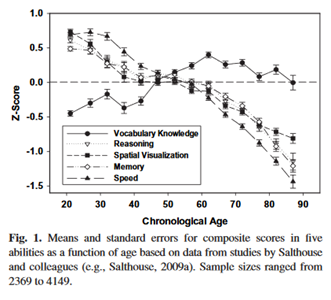

We can look for candidates who demonstrate intelligence. Younger candidates may be better as they haven’t suffered the age-related cognitive decline which can even start before middle age. However, top-tier politicians are elites who seem more resilient to this. And it’s debatable whether high intelligence is a very important asset in political office; Matt Glassman thinks it usually isn’t. Matt Yglesias argues that we should worry more about virtue rather than intelligence when selecting leaders.

An easy, rough way to check candidates for honesty and knowledge isto look at PolitiFact and see whether they have a pattern of making correct statements or not.

Politicians can be corrupt, and CREW is a good source for documenting these problems. There is some evidence that female politicians are less corrupt and make more progress in some policy areas, but most of these studies come from developing countries and the evidence for developed countries like the United States is more limited and mixed.

Be skeptical towards popular narratives about politicians’ personality and authenticity. They are often wrong. This story about Elizabeth Warren is a good example of how politicians can sometimes govern in ways that run counter to how they publicly act and are perceived.

Choosing Viable Candidates

Electability

When choosing candidates to support in primaries, a major consideration is how well they will fare against competitors in the general election. This issue of electability is important, but it is also difficult to judge and contentious. We should always be skeptical towards claims of electability, and should always remember that less electable candidates may still deserve our support if they are significantly more meritorious than the competition. With that in mind, here is the best available evidence on what makes a candidate more or less electable.

Ideology

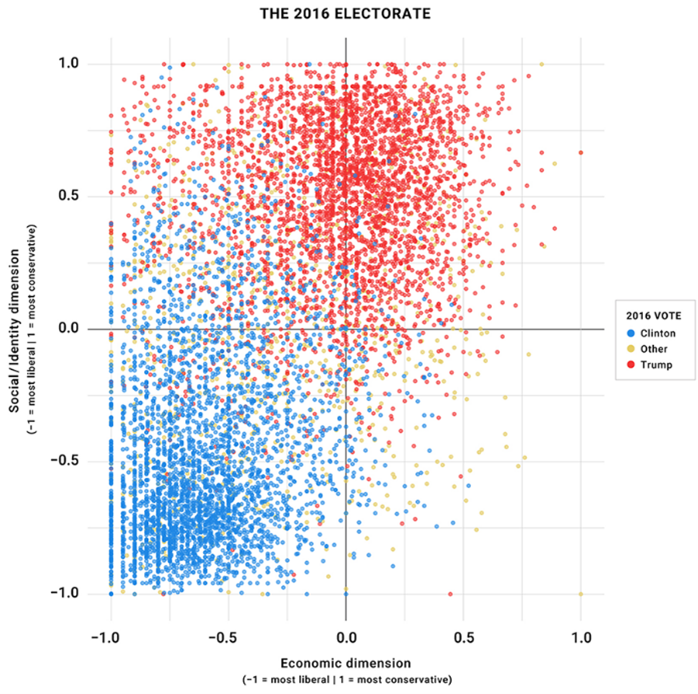

A common sense look at polling data suggests that ideologically moderate candidates tend to be more popular than ideologically extreme candidates, and research on electability backs this idea up. Devin Caughey and Christopher Warshaw start their 2019 paper on electability by reviewing a body of literature showing that moderate candidates are more electable in House of Representatives elections, going back several decades before 2012. They confirmed this pattern for House of Representatives, Senate, governor, state house, and state senate elections up to 2018. Nate Cohn and Alan Abramowitz specifically found that moderate Democrats did better than leftist Democrats in the 2018 midterms. A 2019 survey experiment found that prospective voters seem to be turned off by the leftward lurch of the Democratic party. A 2019 preregistered survey experiment found that voters can be highly supportive of left-wing economic programs, but only when supported by conservative values. A 2020 preregistered survey experiment found that liberal politicians suffer among White voters when they talk about ‘White privilege’ and advocate racial reparations and affirmative action.

The Median Voter Theorem gives a simple theoretical basis for this: moderate candidates are still the best choice for their own party’s extremists, but can capture more of the center. In reality, things are more complicated; elections depend greatly on turnout. An extreme candidate might do more to motivate turnout from the extreme wing of their own party, but usually does even more to provoke turnout from the opposing party. Regardless, recent Democratic Party gains have mainly come from moderate vote-switchers rather than energized turnout.

One challenge to the idea that moderates are typically more electable comes from the fact that Bernie Sanders, who is pretty far left, did comparatively well in prospective polling matchups against Donald Trump during the 2020 Democratic primaries; he only performed about one percentage point worse than Joe Biden on average, and did better than every other candidate. However, this is a flawed argument. First, the polls seemed to mildly overstate Sanders’ electability, as they assumed dubious levels of youth turnout that did not occur in 2016, did not occur in the 2020 primaries, and are prevented by practical difficulties rather than by political apathy (meaning they will probably continue no matter what the nominee’s platform is). Second, Sanders is not particularly extreme when different methods of ideology measurement are used (I will get to measurement methods in a moment). Finally, he benefited from having higher preexisting name recognition compared to all other candidates besides Biden, and name recognition seems to help with this kind of polling (I will also get to this below), so his polling performance against Trump was less impressive. Lesser-known moderate candidates would have done similarly well or better if they had become the nominee and gain corresponding recognition. Sanders did seem more competitive than Hillary Clinton in 2016, but Clinton was uniquely disliked by swing voters, and Sanders was less socially left-wing and more popular in 2016 than he was in 2020. Clearly it is possible for an extreme candidate to be more electable than a moderate, it is just unlikely. David Shor agrees.See this article and this podcast with Yascha Mounk.

Measuring extremity and moderation is a contentious business. You can look at their voting record and political platform, and either make an intuitive judgment or quantitatively measure how much they have in common with their party. For example, Govtrack scores left-right ideology by looking at how often legislators cosponsor bills alongside other members of their party. However, such metrics are sometimes criticized as lacking validity.

You can also look at how many of a candidate’s donors and voters are independents or affiliated with the opposing party. A decent case study for this is Bernie Sanders. Sanders’ voting record and political platform have been more consistently left-wing than those of any other major politician. However, he has a fair amount of support from independents, partially due to having broader cultural appeal than do most progressive leftists. So he’s more electable than you would think from reading his platform. Conversely, Elizabeth Warren is an example of a candidate who wasn’t as left wing as Sanders, but was arguably less likely to gather voters from outside the regular Democratic bloc.

Pollsters will occasionally survey voters for perceptions of candidates’ extremity. This seems like a very reliable metric for the purpose of predicting electability, except that things may change if voters have room to learn much more about a candidate.

It’s probably best to consider all the different ways of measuring moderation and extremity, rather than focusing on just one. Of course, what you shouldn’t do is insist that someone is moderate or extreme by comparing them to political norms in other countries. All the research presented here is talking about moderation and extremity relative to other politicians within our country. Or better yet, just see if a politician's views are actually congruent with swing voters' opinions on particular issues. David Shor says, "I find issue ownership to be a better framework for this than two-dimensional politics. It helps explain certain things like 'People often agree with Dems on economic policy but agree with R's that government should be smaller'".

Other predictors

Debates can matter, but it’s probably difficult to predict and judge debating skill, especially without falling victim to the typical mind fallacy. Rhetoric that appeals to you may not appeal to most other voters. Height is much easier to objectively measure, and taller candidates may have an advantage in debates or perhaps in other contexts.

The electability of female candidates has been widely studied. One methodology is to give surveys of hypothetical candidates and see whether voters prefer men or women; going by this method, a 2021 metanalysis by Susanne Schwarz and Alexander Coppock found that being a woman provides a bonus of about 2 percentage points. A more recent study found that Republican voters are unbiased but Democrats are biased against men. Also, one randomized survey experiment has shown that voters think more highly of female politicians.

Another approach is to see whether female nominees are empirically more successful than male nominees, while trying to control for confounding factors. Schwarz and Coppock summarized such studies in the introduction to their paper, showing that there is no gender difference. An article by Perry Bacon, Jr. included more evidence that there is no gender difference. And a 2020 study of Republican primaries in Illinois also found no gender discrimination.

Some people believe that the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections demonstrated voter bias against female presidential candidates. Specifically, Hillary Clinton did poorly against Trump in 2016, while support for Biden in 2020 was much higher, despite there being no major change in Trump's approval rating in the intervening period. Biden also defeated Sanders by a significantly greater margin in the 2020 Democratic primaries, compared to Clinton’s performance in 2016. Many people who voted for Trump or Sanders in 2016 seem to have done so out of disdain for Clinton, specifically “low opinions of her character and trustworthiness,” and switched in 2020. This comparison seems suggestive of sexism, but is not good evidence. Clinton might have been heavily disliked for other reasons.

Bacon Jr. also summarized the evidence on electability for different racial groups. He found mixed evidence on whether African-American and Latino candidates face a net penalty, and weak evidence that Asian-American candidates get a bonus to electability. A more recent study of Republican primaries in Illinois found that nonwhite candidates received 9% fewer votes, but of course this may not generalize to other states and voters. Meanwhile, David Shor believes that Democrats should run more nonwhite candidates because they actually tend to run more moderate and appealing campaigns compared to woke white candidates.

2019 Gallup polling found that many voters say they would reject presidential candidates who are very old, very young, atheist, or Muslim. Some say they would oppose Evangelical Christian, gay and lesbian candidates. There are some indications that gay candidate Pete Buttigieg had a worse reception among the religious right and Black Southern Democrats in 2020 because of his sexuality, but a 2020 survey found that he still did not fare worse in head-to-head polling against Donald Trump when respondents were reminded about his sexuality.

Polling data

Pollsters sometimes run hypothetical matchups to help primary voters decide which candidate would be most likely to prevail in the general election. There are potential pitfalls to this. First, of course, individual polls can be wrong and it’s best to look at many of them for an average, while also taking into account the problems of particular pollsters. But even when aggregated, such polls can be very inaccurate; when taken for presidential candidates a year out, they have had an average error of 11 points.

However, that doesn’t mean that they are unreliable at predicting differences between potential nominees. Dan Hopkins found that polls for Republican candidates in early 2016 were reasonably predictive of electability.

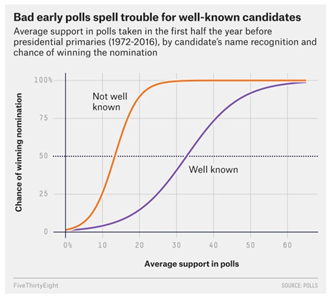

A major problem with this method is that it creates a bias against unknown candidates. 2020 Democratic candidates with higher name recognition did better in head-to-head matchups against Trump, according to the Washington Post (and I replicated this analysis with more candidates and more recent data). If an unknown candidate becomes the nominee, then their name recognition will increase and so will their performance in general election polling.

Another limitation is that these polls are usually weighted to match the general electorate, and actual turnout may follow different patterns. For instance, Broockman and Kalla found that polls were overstating Sanders’ electability because they assumed dubious levels of youth turnout.

Net favorability ratings of candidates can be considered a cruder measurement of candidates’ appeal to the electorate, especially if polls are absent. However, they are similarly affected by name recognition.

Finally, some people treat candidates’ performance in primaries as indications of their electability in the general election. For example, after Biden performed poorly in the 2020 New Hampshire primary, some people thought that this was evidence against his electability in the general election against Trump. However, this is incorrect for two reasons. First, primary voting behavior can be very different from general election voting behavior. Second, every candidate who goes into the general election wins the primary anyway! When we discuss the electability of a candidate, we are assuming that we live in a world where that candidate is victorious in the primaries. Moreover, when we decide to vote for a candidate based on electability, we are further assuming that we live in a world where that candidate just barely wins the primaries, because that’s the scenario where our votes and activism actually make a difference. So it’s best to usually ignore primary outcomes when making electability judgments.

Campaign prospects

Sometimes the best candidate unfortunately has little chance of winning the primary race. There may be a tradeoff between promoting the ideal nominee and promoting a good nominee for whom your votes and activism are more likely to make a difference.

FiveThirtyEight lets us answer this question by comparing polling shares to probabilities of eventual nomination in presidential elections. It turns out that if a candidate has low name recognition and is polling in the 5-20% range, then growing their base can have a tremendous effect on their chances of success. Meanwhile, if a candidate has high name recognition and is polling in the 20-50% range, then growing their base is also very good. Candidates polling below these ranges are less viable, and candidates polling above these ranges are pretty likely to win anyway so additional votes make less difference. Of course this is a simplification; in reality the range of peak tractability for a given candidate could be higher, lower or in between these two models depending on just how well known she is.

Part 3: What To Do In American Politics

Strategy

The appropriate mindset for political engagement is described in the book Politics Is for Power, which is summarized in this podcast. We need to move past political hobbyism and make real change. Don’t spend so much time reading and sharing things online, following the news and fomenting outrage as a pastime. Prioritize the acquisition of power over clever dunking and purity politics. See yourself as an insider and an agent of change, not an outsider. Instead of simply blaming other people and systems for problems, think first about your own ability to make productive changes in your local environment. Get to know people and build effective political organizations. Implement a long-term political vision. And think more about the object level of politics and less about the meta level.